Ancient Venice: A Tour through Art and Architecture

“Embark on a tour of ancient Venice through art and architecture, and discover the magic of the Golden Age.

To truly bring to life the atmosphere that hovered over the lagoon city at the end of the 1700s, there is perhaps no image more emblematic than the fresco “The New World” (1791) by Giandomenico Tiepolo, son of the more famous Giambattista. This painting, currently exhibited at Ca’ Rezzonico – the Museum of 18th-century Venice, a splendid palace overlooking the Grand Canal (Dorsoduro 3136, tel. +39 (0)41 2410100), depicts a small crowd of curious noblemen and townspeople, eagerly waiting to see the wonderful projections of a “magical lantern”, an extraordinary yet ephemeral attraction of modern civilization. The underlying theme of the work is a premonition of the immanent end of an era and an unsuspecting curiosity for the future to come. A bitter metaphor for the current times, under the disenchanted gaze of the two painters, father and son, depicted in profile on the right.

Giandomenico Tiepolo, The New World, 1791, Fresco from the Villa di Zianigo – Portico. Venice, Ca’ Rezzonico – Museum of 18th-century Venice. Courtesy of © Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia

La Serenissima’s golden age was indeed now coming to an end. By this point, political decline was evident: the naval power once enjoyed was now just a distant memory, and Venice was playing an increasingly marginal role on the European scene. The final blow would occur in 1797 with Napoleon handing Venice over to Austria. However, Bonaparte was not immune to the charm of the city, defining piazza San Marco as “the finest drawing room in Europe“.

Throughout the whole of the 18th century, the city was experiencing an extraordinary period of splendor and worldliness. Known as the capital of entertainment and culture, thanks to the freedom of thought promoted by the local authorities against the interference of the Church, Venice attracted a huge number of visitors. It was favored destination on the Grand Tour popular amongst European writers and scholars, such as Goethe and Theophile Gautier. The carnivals, parties, lavish clothing, gallant men, and protagonists such as Canaletto, Guardi and Tiepolo for painting, Canova for sculpture, Vivaldi for music and Goldoni for theater, all contributed to the creation of the legend that is Venice, which continues to attract visitors from all over the world today.

Private and public artistic commissions began to embellish the city’s palaces, churches and buildings, so much so that the Government decided to make an inventory of its rich heritage for fear that it would end up abroad. To understand how the city perceived itself at that time, there is no better painting than “Neptune Offering Gifts to Venice” (1745-50), created by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo for the Palazzo Ducale (Piazza San Marco 1, tel. +39 (0)41 2715911), currently exhibited at the Sala delle Quattro Porte. Pearls, coral and gold coins spill from Neptune’s cornucopia at the feet of the noblewoman representing La Serenissima.

Giambattista Tiepolo, _Ven_ice and Neptune (1745-1750), Sala delle Quattro Porte – Venezia, Palazzo Ducale. Courtesy of © Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia.

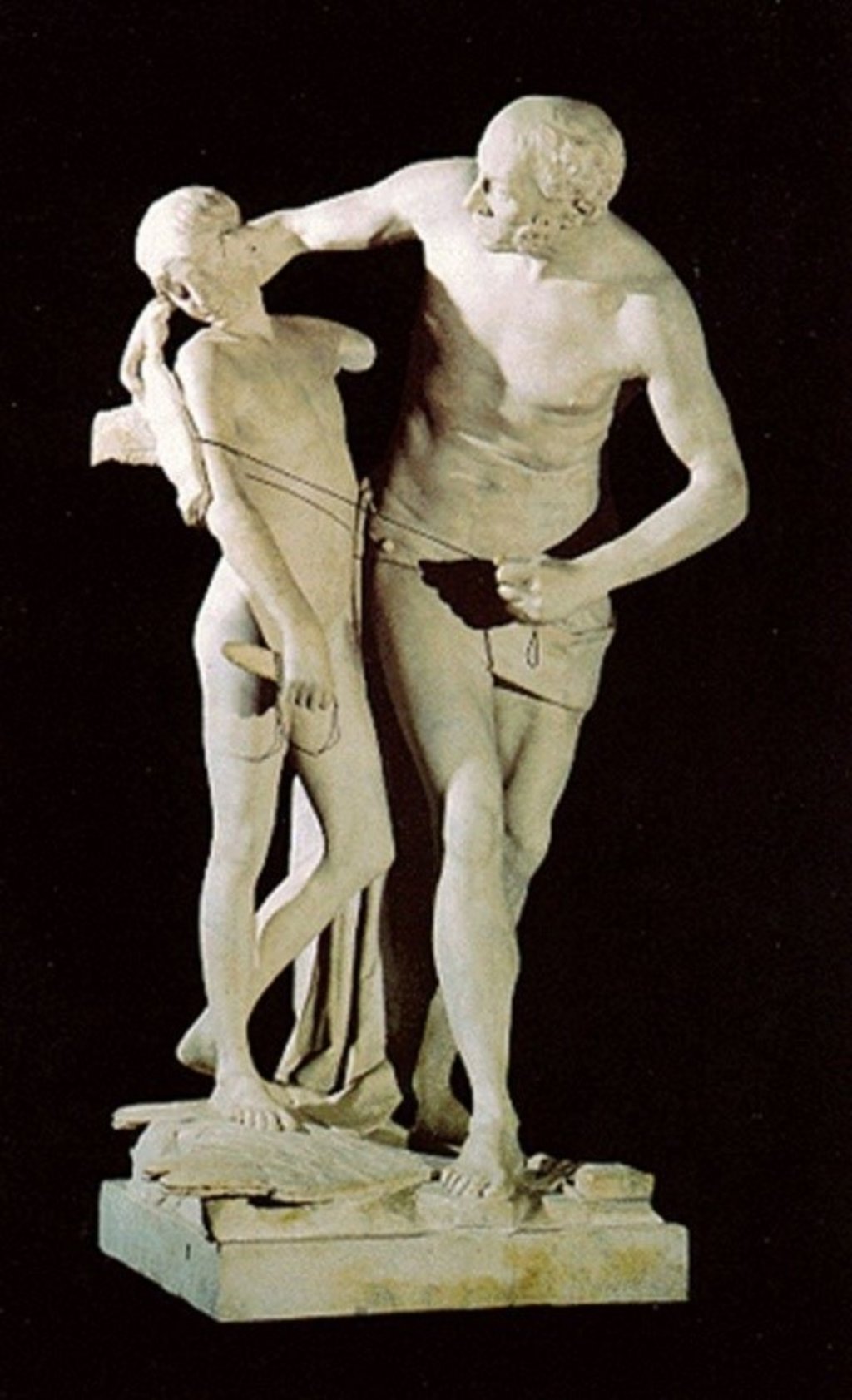

Shortly after, a young stonemason from mainland Italy traveled to Venice to complete an apprenticeship. Canova attended the Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia where he studied design, and also worked in the workshop of sculptor Torretti. In 1779, he was commissioned by procurator Pietro Vettor Pisani to create a marble statue: He produced the splendid Daedalus and Icarus, which can now be admired at the Museo Correr (Piazza San Marco 52, tel. +39(0) 41 2405211), donated to the city of Venice by an heir of the family in 1875. It is believed that it was thanks to proceeds from the sale of the work that the artist managed to scrape together enough money to pay for his trip to Rome.

Antonio Canova, Daedalus and Icarus, 1779, Venice, Museo Correr. Courtesy of © Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia.

The high society of the 18th century could be found in fashionable bars-like the historic Caffè Florian (Piazza San Marco 57), inaugurated in 1720 and still open to the public today-at the many plays performed in the 18 theaters spread throughout the city, and at the concerts and parties that took place on the piani nobili of Venice’s palaces. One example was Palazzo Malipiero (Campo San Samuele, San Marco), a beautiful building overlooking the Grand Canal where senator Alvise enjoyed hosting many social events: Amongst his most frequent guests were Giacomo Casanova and Carlo Goldoni.

“I was born in Venice, in 1707, in a large and beautiful house, situated between the Nomboli and Donna Onesta bridges, on the corner of calle di Ca’ Centanni, in the parish of San Tomà,” wrote Carlo Goldoni in his “Mémories”. The house of the father of modern theater is now open to the public, home to a rich library of theatrical texts (Casa di Carlo Goldoni, San Polo 2794).

A prolific playwright (producing a record number of 16 comedies in a single season and, over the course of his life, an impressive 137), was also the director of the Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo (now theTeatro Malibran, Calle Maggioni 5873, Cannaregio), erected where Marco Polo’s house stood and inaugurated during the Carnival of 1678. Restored during the 1800s, today the theater is an extraordinary example of the architecture of the time. However, the theater is only open during performances.

Alessandro Falca detto Longhi, Ritratto di Carlo Goldoni, Venice, Ca’ Centanni – Casa di Carlo Goldoni. Courtesy of © Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia

Cover photo: Caffè Florian From Piazza san Marco – By S.A.C.R.A. srl – S.A.C.R.A. srl, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41897263“

More Articles With Art

Discover the very best museums and galleries through virtual tours. From London to New York, explore these online museums without leaving your home!

Find everything you need for a fun visit to the York Art Gallery with this comprehensive visitor’s guide.

Discover the top art galleries in London to experience some history and culture on your holiday.

Discover the top art galleries in Manchester to experience culture and history on your next holiday.

Visiting the spas and Georgian buildings of Bath? Check out our visitor’s guide to the Fashion Museum.